Mid-market collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) are a well-worn path in the US. But they are anything but worn out.

Analysis by S&P showed that volumes were up 95% through September last year while volumes in the broadly syndicated loan CLO market dwindled, registering a decrease of 32.5% over the same period.

In fact, their newfound faddish status has been cemented by a rebrand –from middle market to private credit CLOs. As the name suggests the underlying assets no longer remain middle market and private credit is taking centre stage. Even Blackstone has entered the game, raising just under $400mn through a CLO secured by its private credit fund, BCRED.

But is the “rebrand” doing an injustice to private credit CLOs by conflating the terms?

There is no doubt that CLOs remain an attractive way to finance the balance sheet for middle market buyout funds – hence the growth of the asset class. Private credit CLOs are a bespoke asset class designed to open up the sector to a different set of investors.

How does a CLO work?

CLOs initially appeared in the mid-1990s. Commonly known as CLO 1.0, this structure remained common for many years. In response to the financial crisis of 2008, CLO 2.0 offered enhanced collateral and structural improvements. More recently CLO 3.0 has become the dominant structure. Whatever vintage, the basic structure remains the same.

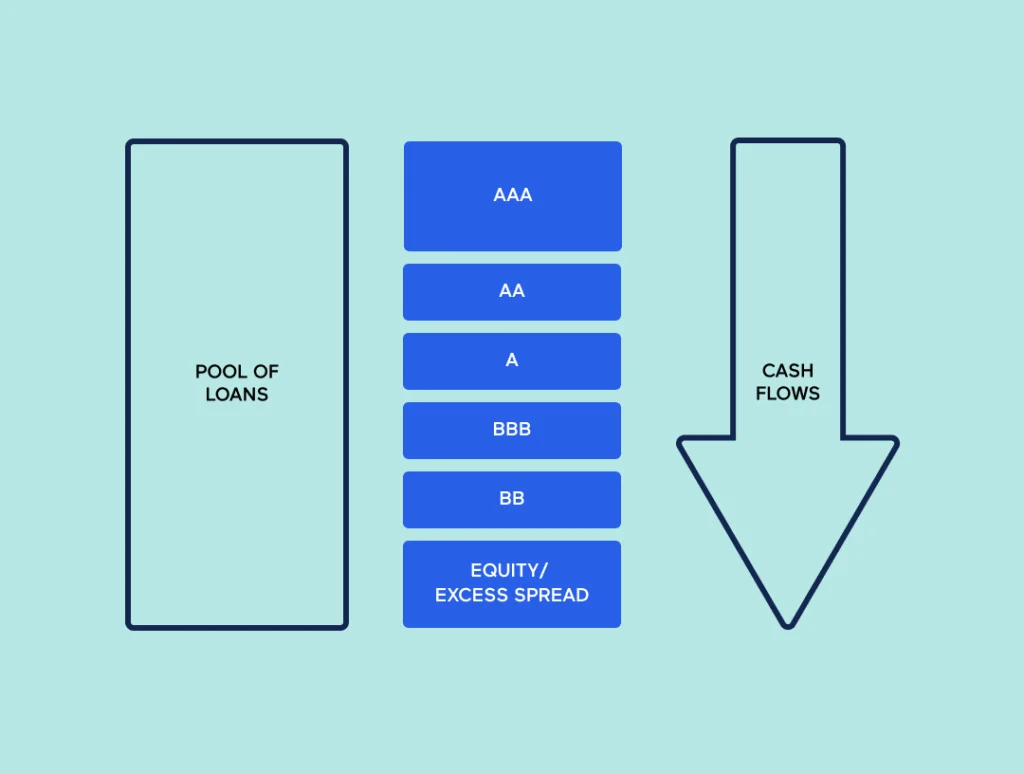

A CLO is a portfolio of predominantly leveraged loans that is securitized and managed as a fund. The securitization process organizes, pools, and structures the underlying loans into tranches of debt and equity.

The different tranches carry different levels of risk and cashflows with the equity tranche carrying the highest risk. Equity payouts are based upon the remaining cashflows – or excess spread – once the obligations for all debt tranches have been met.

Triple A-rated tranches are typically the largest – representing 60-70% of the capital structure. Mezzanine AA to BB-rated tranches as well as the equity tranches are typically a much smaller part of the capital structure.

Typically BSL CLOs offer investors a return based upon the arbitrage between the assets and liabilities of the fund, ie the returns from the underlying pool of assets and the costs associated with running the CLO.

With hundreds of loans forming the pool of assets, investors can get access to a highly diversified portfolio of assets with differing levels of risk and return tailored to investor appetite.

Driven by investor demand

Just as private credit has risen to compete in even the largest deals, the CLO market has found a way to tap into demand for the asset class.

As interest rates have risen, it has offered attractive returns relative to other classes and this has translated into a 30-40bp spread over other CLOs according to some reports.

In addition to attractive returns, the underlying loans tend to offer high levels of security – sitting high in the borrower’s capital structure – and reflect an asset class uncorrelated to wider debt and equity markets.

Historically the entry point to private credit as an asset class has been as an LP in a fund.

The CLO structure not only offers an investment into a pool of direct loans but – significantly – an investment in the form of rated notes. This has opened up the market to insurance companies where the regulatory capital rules make a direct investment in the fund unattractive.

This also explains why private credit CLOs differ from middle-market CLOs. They can be tailored to a select group of investors and marketed selectively without arrangers. In some cases, this could even be a single investor who can absorb the equity tranche in a CLO if the levered part of the notes is attractive enough.

However, securitizing private credit loans is not without challenges.

Direct loans are unrated and, despite the rise of private credit, borrowers tend to be smaller than those in the BSL market. Diversification of the portfolio itself is more limited with fewer loans included.

As a result, the equity tranche in a private credit CLO tends to be larger – often in the region of 25% compared to 10-12% for a BSL CLO. This offers better investor protection as losses are absorbed in the equity and mezzanine tranches.

The equity tranche is also likely to remain with the private credit fund – ensuring that they take the first line of losses on the pool of assets. However, an investor can take an equity tranche if the remaining debt is structured in a way that meets their needs. Even a 25% equity tranche compares favorably with the equity-like position of being an LP in a fund.

For the private credit fund, it offers a diverse – and potentially cheaper – source of funding.

“As private credit grows with more fund managers getting into private credit and existing fund managers raising more funds, there is likely to be a proliferation of private credit CLOs,” explained Sean Solis, Structured Credit Partner, Milbank.

Despite much discussion, private credit CLOs have yet to cross the Atlantic and become a reality in Europe.

The challenge is clear – size matters.

There simply aren’t enough transactions to create a diverse pool of assets or it would take so long to create it that investor returns would be compromised. If a CLO opens in Europe and starts ramping, it could take years to build a suitable portfolio.

An extra layer of complication comes in the form of multiple currencies of the underlying assets. Hedging adds cost while limiting to one currency further reduces the pool of assets that can be selected.

But as someone who has been involved with the European CLO market since its inception, he has no doubt that these issues can be overcome.

“There is an exciting opportunity for private credit CLOs in Europe. But it doesn’t come without challenges: there is a less diverse pool of assets available and there are multiple currencies,” explained Orestis Millas, Head of EMEA CLO New Issue at Morgan Stanley.

With private credit riding a wave of investor interest, it is unlikely to take long before markets find a way to resolve those issues. Undoubtedly that process could be expedited by a mid-market fund with a large portfolio and an existing LP looking to structure their exposure to the private credit market in a slightly different way. It can only be a matter of time.

Conclusion

Whether you call your CLOs middle market or private credit, it is clear that this market will continue to grow – just as private credit itself grows as an asset class. The ongoing tussle between BSL and private credit markets shows that there is a healthy, competitive market with access to multiple sources of leverage.

Stay in touch with all of our latest updates and articles. Sign up now.