Apostolos Gkoutzinis, Head of EMEA Capital Markets and Co-Head of European Leveraged Finance, Milbank LLP will run a session on the principal techniques to safeguard the restricted group in leveraged finance and high-yield documentation.

Key topics covered include:

- The main terminology and key concepts that are the foundations of leveraged finance and high-yield documentation

- The nuts and bolts of the main covenant protections against re-levering, uptiering or leakage transactions

- Current trends in the first quarter of 2025

Please scroll down to view the full recording and read the transcipt.

If you would like to download the slides from this webinar, please submit your details and we will email it to you.

[Introduction]

Covenants in corporate finance documents – whether that is term loans, syndicated terms loans, direct lending transactions or high yield bonds, governed either by English law or New York law – covenants are probably one of the most important aspects of the financial negotiation for a new transaction.

The purpose or a potential restructuring if things go wrong, covenants define what a company can and cannot do.

Covenants are all about discipline and control.

[What typically causes trouble for companies?]

Companies typically in the leveraged finance market get into trouble primarily because of liquidity issues.

There is nothing that covenants can do when the problems have actually arisen on that front for genuine business purposes.

But the covenants have a very significant role to play in creating the original parameters, the discipline within which shareholders and management are allowed to manage the business.

This is to either protect the asset of the enterprise, the assets of the enterprise from dilution or avoid excessive leverage – or a combination.

[It could also] prevent transactions that effectively dilute asset value or the ability of the company to generate cash in a way that either reduces the recoverability of the enterprise for creditors and / or creates liquidity issues.

[It could also] make it impossible to refinance when the time comes.

The key aspect of the covenant protection is obviously the fundamental part that fixed income investors, being Loan investors or High Yield Bond investors, the best ever position for them is to get their money back.

So they are usually very reluctant to allow unlimited flexibility, without the necessary protections, for shareholders and managers to enhance shareholder value in a way that is potentially detrimental for creditors.

So covenants play all of these roles in a financing structure. And today we’re going to spend a bit of time going through the fundamentals and how all of you, as you’re structuring deals or investing money, should be thinking about them.

[Covenants]

The main covenants that we see fall into one of a number of categories.

So we have financial covenants that create financial ratios. Either the ratio of the ability of the company to generate cash to service interest expense known as FCCR, fixed charge coverage ratio or similar metrics.

This is fundamentally how many times the company’s annual cash generation can cover the financing cost or the interest cost.

And the leverage ratio. This means the total amount of indebtedness over the company’s last 12 months EBITDA. This is sort of the more critical measure, obviously, depending on the industry, you can have various formulations of those covenants.

Maintenance covenants require regular testing and they lead to an event at default if the covenant isn’t met. Fundamentally it creates an early warning system if things deteriorate.

The idea of a maintenance covenant is that if the financial metrics of the company deteriorate, the company may not necessarily engage in any value-destructive transaction or credit- destructive transaction.

The company may simply go on about its business and still find itself in a risk of default simply because the headroom in the covenant has deteriorated.

Incurrence covenants which is the market standard in the leveraged finance markets, the Term Loan B market as well as the High Yield Bond market.

Incurrence covenants are tested at a specific transaction that is regulated by the covenant.

So it will be tested if there is an incurrence of indebtedness; the raising of debt; the payment of a dividend or the repayment of junior debt instrument; the making of an affiliate transaction; the making of an investment; the merger of two different companies.

It could be any type of strategic transaction outside the ordinary course of business is going to be covered. So we are going to spend some time going into the details of that.

Covenants limit discretion.

If you want to think about the genesis of this covenant protection in financial markets and their routing in the law, you should think about a board of directors of a company whose duty – the sole duty – is to effectively enhance the value of the company for the benefit of shareholders.

So absent any insolvency or risk of insolvency in every commercial system in the world, the board and the directors – and then obviously through deferred authority the senior management of companies – the sole purpose of their day to day activities is to enhance the shareholders’ value.

So the company is not really run for the benefit of creditors.

And as a result, absent an insolvency or the risk of an insolvency, the creditors only have the four corners of the financing document, the covenant protection, to say to management, shareholders and the board:

We’re fine for you to enhance shareholder value. But given that occasionally the interest of shareholders may conflict with the interest of creditors. For example, it may be a fantastic idea for the board to authorize a major new investment in a particular industry and borrow money to effectuate that investment because they feel that it’s the right thing to do to enhance value.

On the other hand all of that enhanced value is going to be for the benefit of the equity holders.

The debt holders in any structure will only get up to the amount of money they originally invested. They only get their money back.

So an investment which is financed exclusively to the raising of debt in a way that is perhaps only safe for creditors, may create value for shareholders. But it may reduce the value of the credit.

So even though the feeling is that in the ordinary course of the operation of a business, the interest of all stakeholders ought to be aligned and that is usually the mantra – that a business is run for the benefit of everybody.

Legally speaking the reality is that there are a lot of circumstances where a particular transaction may be value accretive for junior creditors or shareholders, and not value-accretive for fixed income investors with a senior secured claim. They want things to be as normal as possible so that they can get their money back and no risky transactions.

For that reason the fixed income markets insist on having sort of the covenant protections that we are going to discuss.

[Overall market dynamics]

Some thoughts on overall market dynamics. This is just my personal views on what’s going on out there.

When looking at covenants, I would say the Syndicated Loan market covenants typically tend to follow market-driven evolution. So long as there is plenty of demand for deals and good credits can go to the market, covenants get loosened up because of the competitive dynamic.

In the Syndicated Loan market covenants tend to follow a market dynamic.

I think the High Yield Bond market is more or less the same, market driven in terms of whether the covenants are loose or tighter. But perhaps – in my experience – in the High Yield Bond market there is a bit more focus on the specific needs of the particular company or the industry, the structure. So maybe there is a little bit of a different flavour in how covenants are negotiated.

If you move beyond the syndicated markets, high yield or loans, into the direct lending space anywhere from the mid-market to large cap direct lending transactions, we see more bespoke and tailored covenant packages.

What I would say as someone who’s negotiated literally hundreds of these agreements. More importantly, as someone who’s advised a lot of companies in the management of those covenants in particular transactions – is this permitted, is this not permitted, how does this work in practice.

Even more so, having done a lot of restructurings and covenant litigation in the English court and New York courts and elsewhere when we see how these covenants actually work in practice.

What I would like to say, is often and this is in my mind an interesting observation, there is quite a bit of divergence between what the market believes that the words mean when these deals are put together – and actually what the law as reflected in court judgments and jurisprudence actually says that the relevant clause means.

I think in a lot of situations people perhaps think that because a particular fact pattern was intended when the relevant law was put into the document, that intention continues to acquire a life of its own into the future.

And that it’s unthinkable that situations that were never really contemplated, had never been contemplated at the time of signing the contract would actually come and use the relevant flexibility or basket.

I want to assure all of you that English law and New York law does not work like that.

What the practice intended, there are some exceptions, but it’s almost never a point in question.

Judges in New York and London will always take a reasonably literal interpretation of what the words mean, irrespective of what people thought as the causal root of the relevant clause, what people may have intended or what people may have tried to solve.

They will look into what the words actually mean on a reasonable, literal interpretation. People would get a dictionary and say: Here it says that as long as this particular transaction is in the ordinary course of business it should be allowed.

People would open a dictionary and say ‘what is in the ordinary course of business’. You may say that because it is an airline, you may think that this could only work in the context of owning and operating an airline.

But if the particular airline has had a number of ancillary businesses in the past or they are using a particular financing structure as a matter of course, then actually ordinary course may mean a lot more things than perhaps what was originally intended.

So keep that in mind as you’re going through these documents.

[Overview of Leveraged Finance Standard Covenants]

I have made an effort to separate Investment Grade from High Yield and TLB. For obvious reasons, there is a lot less attention on covenant protections in Investment Grade compared to the leveraged market.

So if you go down this list, you see the strategic or out of the ordinary transactions that the covenants are supposed to regulate.

Raising financing – which is the incurrence of debt.

Limitation on Liens. So the first flag for those who are less experienced in how these documents work legally.

The Incurrence of Debt regulates literally the raising of money borrowed plus a few other things that are tantamount economically to the borrowing of money.

For example, second contingent liabilities such as letters of credit, letters or guarantee, a performance obligation, drawing on a current account. All of that is tantamount to borrowing money from another person.

The actual act of borrowing money is covered by the debt covenant.

Limitation on Liens is a separate covenant which deals with the separate – but related – matter of whether the money borrowed is secured over assets.

So the combination of the two covenants will always tell you whether secure debt is okay.

If no collateral is being contemplated, Incurrence of Indebtedness covenant will tell you whether you can incur the debt so long as it’s unsecured.

If the debt is secured over any type of asset, then you’re going to have to think about limitation of liens which covers the collateral.

Limitation on Restricted Payments / Investments or Payments of Junior Debt.

Depending on what time of loan finance you want to do, the strawman here is a Senior Secured Bond or Term Loan B, so you are the first ranking.

In the capital structure, if you are the first ranking you have an interest in limiting any value going to creditors or other stakeholders that have an inferior claim. Meaning if you are first ranking, second ranking or subordinated debt creditors, shareholders etc.

So the RP covenant is going to cover things like the payment of dividends, the making of distributions, share buyback program, repaying the principal amount of junior debt and the making of investments. So long as the investment is not a controlling investment it is a minority equity position in another enterprise.

All of these things are covered by what we broadly call the RP protection.

The limitation of transactions with affiliates – it has a similar purpose. If you think about how value generates in an enterprise and can actually go into the wrong hands if you are a fixed income investor.

It could be, for example, through a payment of an enormous bonus to someone who’s affiliated with the shareholders. It could cover arrangements that are effectively paying someone else who is affiliated with the controlling interests in a way that is not on an absolute basis and doesn’t offer fair value.

In my mind, the Affiliate Transactions covenant always comes hand in hand with the RP protection.

Limitation of Dividend and Other Payment Restrictions. This covenant has some historical importance but we see it less and less these days.

It makes sure that the money can flow freely from subsidiaries up to the parent level and there aren’t internal blocks relating to the structural conditions of moving cash. It can obviously create issues for creditors if the creditors are getting claims at the top company level.

Change of Control protection is very important. Fixed income investors are investing not only into a pool of assets which is the enterprise but also investing in a strategy, a senior management and the controlling shareholders.

So the idea is that if the controlling shareholder changes, the investors should get the right to reassess.

The Asset Sales covenant does not prohibit asset sales, it regulates the fairness of these transactions and what the company can get in return for disposing of its assets.

We are going to now see all of that a bit more systematically in the next 25 minutes.

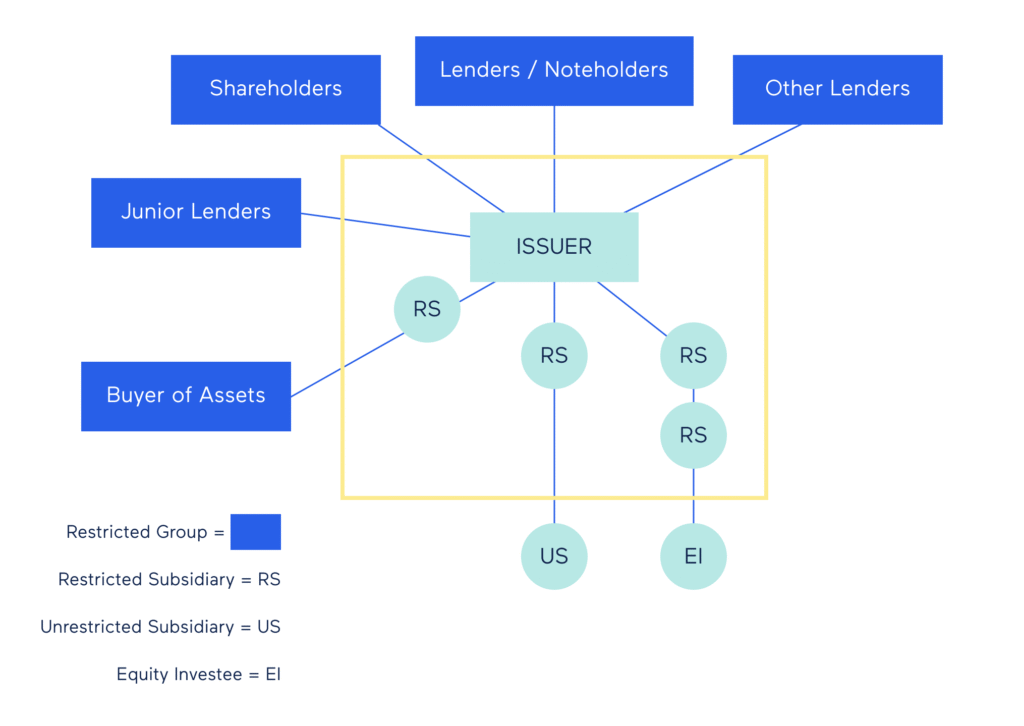

[Restricted and Unrestricted Subsidiaries]

Starting from the fundamental chart that you see here. Hopefully this is familiar to most of you and should allow you to take a conceptual view of the covenant perimeter.

So the first question when it comes to a sensible and an efficient drafting of the covenant packages is always what entities within the enterprise are subject to the covenant.

The main distinction is between the Restricted Group and the Unrestricted Group.

The Restricted Group is the subsidiaries, legal persons that are owned and / or controlled by the issuer of the debt claim in a way that the issuer of the debt claim can control the financial policy, management or operations of that entity.

That usually comes with 51% of the shares. In most legal systems a subsidiary is a restricted subsidiary if the issuer owns and or controls more than 50% of the voting stock because that’s how they control the policies and and the actions of the relevant company.

It could be a 50:50 joint venture but through a shareholders agreement or some other arrangement the relevant subsidiary is actually de facto or contractually controlled by the issuer.

So any entity that is controlled and can be influenced by the issuer is a subsidiary and is automatically a Restricted Subsidiary subject to the covenants.

That is unless it has been designated as Unrestricted Subsidiary meaning for either the beginning of the deal before the financing is put in place or during the life of the financing the relevant entity has been moved conceptually outside the legal restriction.

So you can see here on the chart that the US is the Unrestricted Subsidiary. So this is a controlled entity but the management team has decided that they don’t want that to be part of the covenants.

You may say, ‘well that sounds great, why isn’t every company taken out of the control of the covenants’. Obviously there are consequences that flow from the designation of the company as unrestricted.

If it’s an Unrestricted Subsidiary, it’s not subject to the covenant so the group can handle transactions at that level without being restricted by the covenants.

So this US group can incur unlimited debt so long as they can find somebody to lend to it and leave it there to do some sort of project financing or a major capex program.

But obviously if it’s outside the Restricted Group, the ability of the Restricted Group to support it by way of additional cash endowment, additional investment, guarantees or other credit support is limited. Any type of value that leaves us that we do to go to the Unrestricted Subsidiaries for the creditors is lost.

So there are always pros and cons. What usually tends to happen is entities are part of the Restricted Group when they follow the general financial policy and covenant restrictions.

The management team always has the flexibility to designate a company to an unrestricted subsidiary if they have if they have some special plans. They may want to over leverage it or do something some other strategic transaction. That might be because is in the interest of the shareholders but cannot really fit within the corners of the relevant indenture or credit agreement.

The entity to the right, EI, an equity investee, is neither a Restricted Subsidiary nor an Unrestricted Subsidiary. It is outside the Restricted Group simply because the issuer directly and indirectly does not control an equity investee.

This is probably 20 / 25 / 30% minority interest without control rights. And given that the issuer does not control EI, the issuer does not want EI to be subject to covenants and then be restricted.

If you don’t control an entity and that entity goes on and carries out its own independent policy then the issuer could find themselves violating covenants with the actions of another party that they don’t control.

So equity investees and Unrestricted Subsidiaries are outside the group. Restricted Subsidiaries and the issuer are inside the covenant group.

Guarantors are always a subsidiary. The giving of a guarantee will always be by restricted subsidiaries within the restricted group.

[Potential Financial Ratios and Reporting]

Potential financial ratios and reporting, two things can be said.

First, the reporting, there are exceptions, but most of the market follows faithfully the distinction between always reporting all the ratios as they apply to Restricted Subsidiaries and the issuer.

And then the reported financial statements obviously cover the entire group but the group includes unrestricted subsidiaries. Creditors usually want to know what is the individual performance of the Unrestricted Subsidiary or the financial performance of the unrestricted subsidiary group as part of the structure, certainly in the bond market.

Footnote disclosure can be provided for any transactions of the Unrestricted Subsidiary so that the market can follow the evolution of the unrestricted subsidiary cash flows, liquidity and financial position.

[Guarantors]

The concept of a Restricted Subsidiary and the concept of a Guarantor, legally are two distinct entities. A subsidiary can be a Restricted Subsidiary without being a Guarantor.

A Guarantor will always be a Restricted Subsidiary.

The concept of a guarantee is a very important concept. It offers a direct claim for the benefit of the creditors against the legal entity. And the legal entity is also subject to the covenants. So both the Restricted Subsidiary and the Guarantor.

Unrestricted Subsidiaries that do not have a guarantee will be subject to the covenants but in the event of an insolvency would not really be capable of being sued for payment by creditors.

[Limitation on Indebtedness Covenant]

Now, I think we will spend a bit of time on the Limitation on Indebtedness covenant which is probably one of the most important protections for creditors. The Limitation on Indebtedness covenant limits the incurrence of additional debt based on the ability of the company to service its overall debt.

So what usually tends to happen in credit agreements and bond indentures is that there will be a very wide and all-encompassing prohibition against the incurrence of any debt.

Unless the incurrence of that debt after giving effect to the proceeds and the use of proceeds, for example refinancing or other mutual proceeds, ensures that certain ratios that are specifically negotiated are met.

So that’s the first major limitation and it is a very all-encompassing restriction.

No additional debt is allowed by any restricted subsidiary unless following the incurrence of that debt, based on the last 12 months financial performance of the company calculated on a pro forma basis, the ratio of fixed charges to adjusted EBITDA, which is the major FCCR ratio is met at the 2:1 level.

Or the debt to adjusted EBITDA ratio is satisfied.

So either a leverage ratio is met or a fixed charge coverage ratio is met. Then there is no additional debt capacity.

These calculations are always occurring pro forma for the transactions that are happening simultaneously. So if the new debt is raised to repay old debt then obviously we calculate the last 12 month fixed charge ratio as if the old debt had been repaid and the new debt had been incurred at the beginning of the 12 month period.

So all calculations are giving real effect to all the transactions that are factually linked to the transaction that we are testing.

And also by giving effect to acquisitions and or disposals of assets or other strategic transactions depending on the deal obviously. The drafting can be quite elaborate.

The idea is that all strategic transactions that have happened in the last 12 months, which is a common measurement period, or any other transactions factually, concurrently happening at the time of the incurrence of the debt – for example an acquisition or a new disposal – all of these things will go into the numerator and the denominator of the ratio.

So the measurement of the ratio is as close to the reality of the situation as possible.

I’ll give you a couple of examples.

Debt is raised to acquire a new business. This acquisition follows a disposal of a major business division three months ago.

So let’s say at the end of June, debt is raised to acquire a new major business And this acquisition follows the disposal back in March of a disposal of another business line.

So we start with the last 12 months of reported EBITDA. But we have to subtract the EBITDA attributable to the business that was sold. Otherwise we are measuring cash flows that are just not there.

Then we have to add in the new EBITDA that he’s been acquired by the group in connection with the new acquisition.

Also any other transactions that are factually supportable that are covered by the wording of the measurement of the ratio.

There is usually a very long list of adjustments, the cost effect of certain initiatives in connection with a new acquisition or initiatives in connection with the old disposal. Usually all of these adjustments tend to increase the cash flows going into the ratio.

The idea is that you get as close as possible to an illustrative ratio of the recurring financial performance of the business – assuming all the strategic transactions that have happened in the last 12 months or are happening – in connection with the financing that is being tested, have occurred.

So it’s far from a simple calculation.

It follows the logic of let’s normalize cash flows. Let’s exclude some of the items. Let’s take the benefit and / or lose the benefit of items that are not going to be there (they are one of the exclusions). Let’s include EBITDA that is being acquired and exclude EBITDA that is being disposed of.

Then you come to the ratio calculation and it’s a pass or fail test. There is no prize for nearly missing the ratio.

[Additional Baskets]

If the ratio is missed then you fall back on the typical formulation which is all the additional baskets. We’re going to go through some of them very quickly in the next few minutes.

The idea is that there are fundamental ratios. If the ratios are met, the transaction can go ahead. If the ratios are not met, the transaction can only happen if they are being met or they satisfy one of the relevant baskets.

So that is sort of the usual, standardized approach where there is a big initial enabling provision under the ratios. Then you have all the other baskets like the credit facility basket, purchase money or cap lease basket, contribution basket, the general basket for all sorts of purposes.

The idea is that a company needs to get the flexibility to carry out some of these transactions iIrrespective of the evolution of the financial metrics.

Simply because the EBITDA of the company has suffered temporarily and the incurrence of the debt cannot occur under the ratios, doesn’t mean that the company’s not going to get a refinancing basket.

The finances are coming due and the company – to the extent that they can borrow – should be able to refinance existing debt or have some general debt basket for general purposes.

So there is a long list of exceptions to the ratio rule which are either based on the use of proceeds of those exceptions or like the general debt basket is for any purpose.

Then some of the other baskets follow a particular logic. The idea is that existing debt should always be refinanceable under the baskets, to the extent that there is a willing lender to refinance existing debt.

The company should never be in a position that they don’t have the ability to refinance.

Otherwise, the covenants effectively become maintenance covenants. The logic that the syndicated markets apply is that the covenants should be tested on an incurrence basis.

[The Liens Covenant]

The liens covenant is always coming on top of the debt covenant. The idea that you don’t only test the indebtedness covenant, you have to find capacity to incur the lien.

Typically in a well-drafted indenture or credit agreement, the two covenants are synchronized and there is a logic that follows through these two covenants.

The idea is that there is usually an overall limit of secured debt that the company should be able to incur pro forma for new acquisitions, pro forma for disposals.

So any and all secured debt within that overall senior secured pool should be allowed. If that senior secured leverage ratio has been maxed out because all the relevant debt has been incurred, then we have to go through the same logic of finding specific baskets for specific purposes.

If the debt that we’re refinancing was secured, we should be able to get collateral for the refinancing debt.

If the company gets a basket to incur debt to acquire plant and equipment up to a certain threshold, we should be able to offer collateral over the machinery, inventory, plant or the equipment which is purchased with the new debt. That’s the cap lease lien.

[The Restricted Payment Covenant]

We will have a few more minutes on the Restricted Payment covenant and then we will stop for questions.

The Restricted Payment covenant is not really one covenant but several covenants combined in one.

First is a limitation of paying dividends or transactions that have the equivalent effect of share buybacks or other distributions to shareholders.

The idea here is that in the high yield market there’s usually like a fundamental handshake between shareholders and debt holders that when it comes to dividends, 50% of the net profit of the group can go out as dividend payments and 50% stays in the business.

Plus, in addition to the 50%, there are Builder Baskets. These are more technical baskets which allow certain dividends to be paid depending on whether the company is a listed company or has issued other equity-linked instruments, for example a convertible bond that is converting to equity builds the dividend basket.

The idea is that so long as equity value is created, an equivalent amount or an equal amount of equity value can go up to the shareholders.

So in the Term Loan B market, the builder basket is usually complemented by available amounts for distributions. The available amounts aren’t really tied to the generation of accounting net income, which is more of a high yield bond concept. The available amount is mostly tied to cash availability, like free cash flow that is available after servicing of debt and other operational expenditures.

The idea is available amounts can be used for distribution. So there is a little bit of different logic there between the bond market and the Term Loan B market.

Albeit in all these markets, especially for the top tier Sponsor deals in the European space, have begun to converge. We are definitely seeing a lot of TLB concepts going back into the High Yield documentation and a lot of the High Yield concepts going back into the credit agreements for TLBs.

I don’t think it is tenable any more to think of credit agreements vs High Yield Bonds, there is wholesale convergence of all of these terms.

I think we are at the 45 minutes. Lots to cover but hopefully we can cover some additional points through the Q&A.

[Question] You talked a little bit about the differences between the High Yield Bond market and the TLB market, can you expand on that?

The High Yield Bond market was developed primarily in the U.S., governed by New York law and following the American approach.

The European Term Loan B market has borrowed a lot of the concepts from the High Yield Bond market.

The High Yield Bond market has also incorporated quite a lot of the LMA standard documentation from the Syndicated Loan Market, which was originally an investment grade market for high quality loan paper.

Right now, in most transactions there is a great deal of convergence. I think there are some additional restrictions in relation to permitted acquisitions or permitted investments in credit agreements that are not exactly matched in the high yield space.

There are certain prohibitions of loan purchases which are unique to the Syndicated Loan market.

I think we mentioned one in relation to Restricted Payments where I think the idea of Available Amount for distribution is mostly based on cash available versus net profit generated which is the 50% builder basket for high yield.

Guarantors and guarantor coverage is quite a big difference. There is always a bit more focus in the TLB market for a guarantor coverage that is like a maintenance test – it has to be met. High yield is more of a ‘day one the test has to be met’ market.

But obviously if there is a TLB in the structure, the TLB is getting guarantor protection so that High Yield will always get it.

There are technical differences in deals where there is a High Yield Bond and a Credit Agreement side by side. In some of the top tier sponsor deals I think the convergence is even more pertinent and that way you see covenant packages that are completely harmonious across the two.

From the perspective of the sponsor, it is reasonable if you have a bond and a TLB side by side, it makes sense for the flexibility and the covenant packages to be harmoniously co-existing. So that is where you get most of the convergence.

Fundamentally the ideas are similar. The differences are in the detail.

[Question: We have had a question in about whether the interpretation of judges according to UK or US law is more borrower or lender friendly.]

It’s a great question. I can say with a lot of confidence that American judges and English judges, they don’t take sides in the debate pro-borrower or pro-creditor.

Generally speaking, both Anglo-American legal systems are pro-creditor in the sense that in the insolvency procedures and distressed restructurings the two systems encourage rehabilitation by creditors’ out of court settlements, support of creditors.

The idea is that the two legal systems will allow all sorts of tactics and machinations, in a positive way, so that the enterprise survives. Both legal systems generally speaking have an aversion to liquidation and insolvency. They want to give as much power as possible for a solvent solution to be found.

That’s a general comment about the attitude and the philosophy of the restructuring or insolvency legal regimes.

When it comes to interpretation of the covenants of solvent businesses. I think I can say with confidence that both the US and English jurisprudence look at covenants strictly. They look at what they say and they give the ordinary meaning to the words.

They’re not looking for philosophical concepts behind the words. They’re not looking at the intention of the parties behind the words. If the document says that a particular course of action is allowed, even if the outcome of that allowance may be commercially absurd. If the words are clear and the words are not contradicted by other words in the same agreement, the fact that perhaps it leads to unintended consequences is not going to be a consideration for English and New York law judges.

There a couple of variations which I’m going to cover.

Obviously if the wording on the page is not clear. If the wording on, say, clause A is clear but contradicts or doesn’t sit well with the wording three pages down, so that there is some internal inconsistency – the judges will intervene.

They will find the interpretation that gives the best commercial efficacy to the contract.

So the judges in other words will not be very activist in either English or New York law, unless the contract itself is unclear or internally inconsistent or contradictory. Then they will try to intervene to see what is the best commercial efficacy.

One slight difference between the two systems.

Having been on numerous restructurings, including some that have been litigated, one slight difference is that there is such a thing as the covenant of good faith in New York law governed contracts.

The covenant of good faith provides an overarching umbrella.

If the actual words in the contract are used by the parties in a way that is viewed as patently absurd or abusive in a way that that none of the parties had ever contemplated would be used, so that it makes the contract devoid of its meaning.

So it might be that the words stick together nicely but the actual outcome makes a mockery of the commercial soundness of the arrangement, New York law will say you can’t go there. You can not do a transaction, that albeit may comply technically with the wording of the contract, but effectively upsets the very essence of that contract.

It is a concept that New York judges apply very, very, very sparringly. They’re not willing to do that sort of thing willingly.

[Question: What kind of trends you are seeing in Q1 and what are the most contested points in the market today?]

Every time we launch a deal and we get pushback in the market through flex of items in a TLB or renegotiation or pushback on a High Yield Bond, its always around six or seven related issues.

For example, RPs, synergies and and the cap on getting the pro forma benefit of getting the synergies; whether there is going to be a cap or whether it is entirely uncapped; available amounts; the size of the freebie basket and some of the ability to do second lien financings.

We also see affiliated transaction concepts and some of the named loopholes – everybody is using named terms like Envision, PetSmart, Chewy, Niemann Marcus, Serta, J Crew and all of these points that are coming out of distressed restructurings.

These are all provisions in documents that provide certain flexibilities that perhaps were never intended.

So there is an increased focus on switching off some of these protections.

Specified asset sales and what are the right sort of leverage thresholds for permitting dividends to be paid out of asset disposals.

These are probably the areas that the market is focused on.

Obviously overall level of debt capacity from day one and overall dividend distribution level.

Over the last 18 to 24 months, the market continues to be very generous with the covenants in the right deals, the credits that everybody wants to be in. And the market continues to be a bit more careful and more selective with the more difficult credits.

Stay in touch with all of our latest updates and articles. Sign up now.